The U.S. Response and Deteriorating International Relations

- andresquintiliani2

- Nov 18, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 23, 2020

Due to Japan's increased involvement in Manchuria and Southeast Asian regions, the United States began to take action. Major restrictions were placed on Japan, which made the Pacific War an inevitable reality.

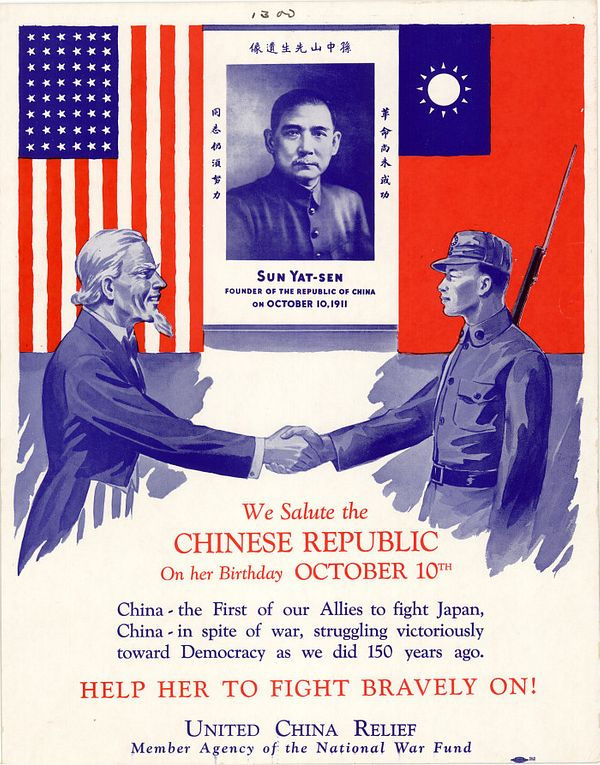

American Pro-China propaganda poster trying to relate China's struggle for independence to that of the United States. Distinctly shows that the United States was extending their support.*“The United States had a "Wilsonian" or "neo-Wilsonian" approach to Japan in the late 1930s, that is, an international system dominated by the Anglo-Saxon Powers, primarily Great Britain and the United States, with Japan as a cooperating member."*

As Japan was locked in to building up Manchukuo and continuing its path to Asian imperialism, the United States began to catch on. Japan’s goals were met with increased American disapproval, and in order to determine the driving forces behind the Pacific War, it’s imperative to understand Japan’s International Relations during the Twentieth Century. As Harry Wray notes in the introduction to Pearl Harbor Reexamined, many scholars today believe that Japan was not that connected to the goals of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, nor were they the sole perpetrators in the Pacific War while the U.S. was the victim.* The United States viewed China as a strategic acquisition and since they were more involved in the Pacific with the annexation Hawaii and the Philippines, they saw an Open Door Policy as the best plan of action for China. The policy was declared in 1900, and while it really did not signify much, it caused Americans to start thinking along the lines of them being China’s protector against a “predatory Japan” so to speak.* As Wray goes on to illustrate, the U.S. believed “the Yankee of the East was no longer an admired friend, but a rival”.* Similarly, Japan really did fear that America’s increasing sphere of influence in China was going to lead to Western powers seizing full control of a neighbor state that Japan both wanted and felt like they were entitled to have.

Because much of the international focus was containing Nazi Germany and Europe, the U.S. was able to be more assertive with Japanese affairs in the Asia-Pacific region. Only if the U.S. began to question their own policies in the region, relating to increased Japanese emergence would they shift more focus, but at the time Americans were less effected by the decisions in the Asia-Pacific region and they left little impressions on leaders.* On the other hand, decisions like the reduction in the warship ratio as well as the Open Door Policy in China and the lack of recognition for support in World War I, greatly frustrated Japan and caused them to start to view the Western powers as an enemy. Nevertheless, in 1936 they signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Germany and Italy, thus founding the Axis Alliance. This was a clear sign that militarists were in full power in Japan and were advocating for an aggressive foreign policy.

Was this an impulsive decision targeted at the United States? Maybe it was a build-up of inferior treatment by the West, but one thing was for sure: now that the pact was signed with the enemies of the West, there was no way the U.S. could support Japan. One example came with Japan’s struggle to end the war with China in 1940, as Japan asked for the U.S. to back off from their support of China in order to give Japan some kind of power and recognition. The U.S. refused to agree, mainly because they were seen as the enemy.* Similarly, the U.S. decision to give China loans but place embargoes on Japanese exports had no doubt affected Japan, but they were not carefully drawn out by the U.S., again because of the fact that much of their concern was focused on Europe.* In this way, Iriye believed that America could have done more to strengthen policies toward Japan, rather than deteriorate them.*

In his chapter in Pearl Harbor Reexamined, Gary Dean Best places much blame on President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his foreign policies. Roosevelt also wanted authority in China and at the same time wanted to be hostile toward Japan. In his mind, Japan was a threat to the status quo, so many of his foreign policies were rooted in prejudices.* He was willing to go to war with Japan because of China and ally himself with the Soviet Union, yet by doing so, he was backing the Soviet’s spread of Communism. As historian John V.A. MacMurray put it, “nobody except perhaps Russia would gain from a victory in such a war."* Many people advocated for FDR to promote economic recovery and be an economic asset for other countries after the Great Depression. The economic strengths that the United States possessed at the time could help alleviate tensions and promote peace, but FDR turned the other cheek and the result was increased political aggression from countries like Japan. They viewed the U.S. as a fragile country that emitted a sense of bravado and weakness, but these were views that could’ve been avoided had FDR agreed to help stimulate struggling countries in the aftermath of the depression.

Going back to the narrative that America was mainly preoccupied with Europe, many U.S. leaders had clouded judgements of Japan’s desperation, both in their struggle to recover from the depression and in their struggle for power in Asia. Not many people actually believed Japan was capable nor wanted to go to war with the U.S. The problem was, however, that the U.S. never recognized Japan’s desperation that came as a result of the U.S. soiling their economic goals as a country.* Although many diplomatic historians believe that the Pacific War could have and should have been avoided*, the decisions made by the U.S. that at the time were viewed as marginal on their end, broke off many ties .

Author Ikei Masaru notes that there were multiple “mismanagements” of U.S. policy toward Japan before the war. The U.S. disregarded the seriousness of not providing proper aid to Japan during the depression. Similarly, they acted impulsively in placing embargos on weapons and loans to Japan and suspending all trade with Japan, despite these decisions being opposed by business elites and the U.S. State Department.* Another example of their mismanagement goes back to China. Both Japan and the U.S. had opposing interests: The U.S. believed China was worthy of modernization and independence, while Japan of course believed China should be completely under their control.* The last example of mismanagement by the U.S. was their belief that Japan was Fascist because they were associated with Germany and Italy. However, Japan’s joining the Axis was merely a defense mechanism designed to put an end to Western influence and involvement in the Pacific.*

These mismanagements in international relations caused Japan to become more and more motivated to retaliate against the U.S. and by 1940, Japan was no longer willing to accept being subordinate: they set out to keep their goals of Asian conquest alive, this time making sure they eliminated those who got in their way.

Anti-Japanese propaganda video during WWII that stressed Japan's exaggerated desires to conquer the whole world. The significance is that the video is trying to build up this "fear factor" toward Japan and their capabilities.*

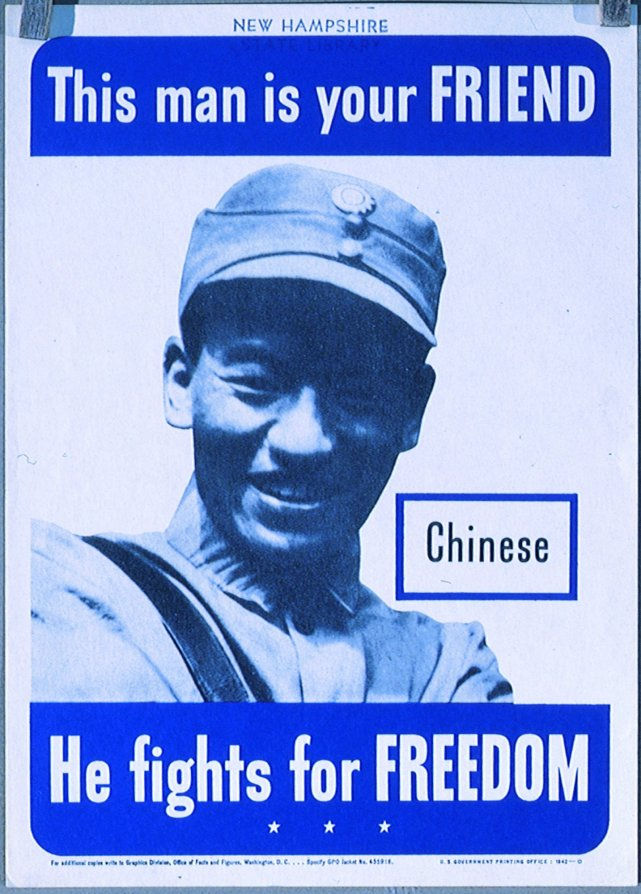

Another Pro-China propaganda poster from the U.S., basically acting as a "know your ally" lesson for Americans, as they struggled to help China push out Japan. The question is, did leaders like FDR view China as a "friend?"*Footnotes:

1. United China Relief Poster. The Diplomat, Diplomat Media, 21 Aug. 2015, thediplomat.com/2015/08/when-the-us-and-china-were-allies/.

2. Conroy, Hilary. "Ambassador Nomura and His "John Doe Associates": Pre Pearl Harbor Diplomacy Revisited ." Pearl Harbor Reexamined: Prologue to the Pacific War, edited by Hilary Conroy and Harry Wray, Honolulu, U of Hawaii P, 1990, 97.

3. Wray, Harry. "Japanese-American Relations and Perceptions, 1900-1940." Pearl Harbor Reexamined: Prologue to the Pacific War, edited by Hilary Conroy and Harry Wray, Honolulu, U of Hawaii P, 1990, 2.

4. Ibid, 5.

5. Ibid, 4.

6. Iriye, Akira. "U.S. Policy toward Japan before World War 2." Pearl Harbor Reexamined: Prologue to the Pacific War, edited by Hilary Conroy and Harry Wray, Honolulu, U of Hawaii P, 1990, pp. 18.

7. Ibid, 14.

8. Ibid, 23.

9. Ibid, 24.

10. Best, Gary Dean. "Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the New Deal, and Japan. "Pearl Harbor Reexamined: Prologue to the Pacific War, edited by Hilary Conroy and Harry Wray, Honolulu, U of Hawaii P, 1990, 30.

11. Ibid, 31.

12. Emmerson, John K. "Principles Versus Realities: U.S. Prewar Foreign Policy toward Japan." Pearl Harbor Reexamined: Prologue to the Pacific War, edited by Hilary Conroy and Harry Wray, Honolulu, U of Hawaii P, 1990, 44.

13. Best, Gary Dean, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the New Deal, and Japan, 27.

14. Masaru, Ikei. "Examples of Mismanagement in U.S. Policy toward Japan Before World War II." Pearl Harbor Reexamined: Prologue to the Pacific War, edited by Hilary Conroy and Harry Wray, Honolulu, U of Hawaii P, 1990, 48.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid, 49.

17. Anti-Japanese Propaganda Film Made during World War Two with the Objective of Portraying the Japanese as a Race of Brutal Savages 1940's. Huntley Film Archives, 1940s.

18. Chinese Soldier Poster. The Diplomat, Diplomat Media, 21 Aug. 2015, thediplomat.com/2015/08/when-the-us-and-china-were-allies/.

Comments